The Final Debt Reckoning for the US: What De-Leveraging Looks LIke

Below are excerpts from an excellent article in the WSJ summarizing the current debt position of the US. I found it interesting because everyone talks about de-leveraging the US economy, but no one describes what it is going to look like. Well this is what it looks like. Another added cost/benefit of the de-leveraging is that it will uncover many (if not all) of the weaknesses in the financial system. Let us face it this process is still unfolding and there is more pain to come. No amount of election year sloganeering is going to solve these problems anytime soon. Text in bold is my emphasis.

The U.S. is at the receiving end of a massive margin call: Across the economy, wary lenders are demanding that borrowers put up more collateral or sell assets to reduce debts.

The unfolding financial crisis -- one that began with bad bets on securities backed by subprime mortgages, then sparked a tightening of credit between big banks -- appears to be broadening further. For years, the U.S. economy has been borrowing from cash-rich lenders from Asia to the Middle East. American firms and households have enjoyed readily available credit at easy terms, even for risky bets. No longer.

Recent days' cascade of bad news, culminating in yesterday's bailout of Bear

Stearns Cos., is accelerating the erosion of trust in the longevity of some brand-name U.S. financial institutions. The growing crisis of confidence now extends to the credit-worthiness of borrowers across the spectrum -- touching American homeowners, who are seeing the value of their bedrock asset decline, and raising questions about the capacity of the Federal Reserve and U.S. government to rapidly repair the problems.

Global investors are pulling money from the U.S., steepening the decline of the U.S. dollar and sending it below 100 yen for the first time in a dozen years. Against a trade-weighted basket of major currencies, the dollar has fallen 14.3% over the past year, according to the Federal Reserve. . . . .

. . . . Lenders and investors are pushing up the interest rates they demand from financial institutions seen as solid just a few months ago, or demanding that they sell assets and come up with cash. Banks and Wall Street firms are so wary about each other that they're pulling back. Financial markets, anticipating that the Fed will cut rates sharply on Tuesday to try to limit the depth of a possible recession, are questioning the central bank's commitment or ability to keep inflation from accelerating.

There are other symptoms of declining confidence. Gold, the ultimate inflation hedge, is flirting with $1,000 an ounce. Standard & Poor's Ratings Services, a unit of McGraw-Hill Cos., predicted Thursday that large financial institutions still need to write down $135 billion in subprime-related securities, on top of $150 billion in previous write-downs. Ordinary Americans are worried. . . . .

. . . . "Clearly, the whole world is focused on the financial crisis and the U.S. is really the epicenter of the tension," says Carlos Asilis, chief investment officer at Glovista Investments, an advisory firm based in New Jersey. "As a result, we're seeing capital flow out of the U.S."

That is a troubling prospect for a savings-short, debt-heavy economy that relies on $2 billion a day from abroad to finance investment. It is raising the specter of the long-feared crash in the dollar that could further rattle financial markets and boost U.S. interest rates.

Though the risks of an unpleasant outcome are worrisome, the effects of Fed interest-rate cuts and fiscal stimulus have yet to be fully felt by the U.S. economy. Moreover, the combination of a weakening dollar -- which remains the world's favorite currency -- and still-growing economies overseas is boosting U.S. exports and offsetting some of the pain of the housing bust and credit crunch.

But while cash continues to pour into the U.S. from abroad, this flow has been slowing. In 2007, foreigners' net acquisition of long-term bonds and stocks in the U.S. was $596 billion, down from $722 billion in 2006, according to Treasury Department data. Americans, meanwhile, are investing more of their own money abroad.

Hopes are fading fast that the U.S. economy was suffering from a thirst for liquidity that standard Fed remedies could quench. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, speaking in Washington yesterday, said he sees "an increasing risk that the principal policy tool on which we have relied -- the Federal Reserve lending to banks in one form or another" -- is like "fighting a virus with antibiotics."

Bob Eisenbeis, a former executive vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, says the problem is more than an inability to find ready buyers for assets. "It is time to step back and recognize that the current situation isn't a liquidity issue and hasn't been for some time now," said Mr. Eisenbeis, the chief monetary economist for Cumberland Advisers. "Rather, there is uncertainty about the underlying quality of assets -- which is a solvency issue, driven by a breakdown in highly leveraged positions."

President Bush, speaking in New York and in a television interview yesterday, showed little appetite for further action. Detailing the steps the administration has already taken, the president in a speech knocked a couple of pending proposals. "Government policy," he said, "is like a person trying to drive a car on a rough patch. If you ever get stuck in a situation like that, you know full well it's important not to overcorrect -- because when you overcorrect you end up in the ditch."

But few in markets and elsewhere are convinced that the worst is over for the U.S., as each player moves to protect its own interests against potential calamities seen as improbable just a few months ago. Bear Stearns reassured investors earlier this week that it was solvent, but speculation that Bear faced a liquidity crunch had some traders and hedge funds moving to limit their exposure to it. Yesterday, J P Morgan Chase & Co. and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York offered emergency funds to keep the troubled investment bank afloat.

The loss of confidence is now spreading beyond the biggest banks, with their well-publicized losses on subprime and other risky assets, to regional and small banks. In the fourth quarter, U.S. banks reported their smallest net income -- a total of $5.8 billion -- in 16 years, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

There's little sign yet that the worst is past. The "moment of recovery" is when forecasters turn out to be too pessimistic, says Mr. Summers. That point hasn't likely arrived. A Wall Street Journal survey of more than 50 economic forecasters in early March found a profound shift toward pessimism: About 70% say the U.S. is currently in recession, and on average they put the odds that this recession will be worse than the past two mild, short recessions at nearly 50%. Most expect house prices to decline into 2009 or 2010.

This couldn't come at a worse time for U.S. homeowners. American household debt has more than doubled in a decade to $13.8 trillion at the end of 2007 from $6.4 trillion in 1999, the vast majority of it in mortgages and home equity lines, according to Fed data. But the value of U.S. householders' biggest asset -- their homes -- is now falling.

The response of the Republican White House, Democratic Congress and Federal Reserve have been substantial. President Bush and Congress, with remarkable speed, agreed to a $160 billion fiscal-stimulus package that will put money in consumers' wallets soon. The Fed already has cut interest rates by 1 1/4 percentage points this year, and markets anticipate another 3/4 point cut on Tuesday. The Fed has moved to buy $400 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities for its $800 billion total securities portfolio in an effort to jolt that crucial market back to life and prevent rising mortgage rates from further depressing the U.S. housing market.

While there is continued debate about how to treat the current disease, there is a consensus emerging on the causes. "Soaring delinquencies on U.S. subprime mortgages were the primary trigger," the heads of the Treasury, Federal Reserve and Securities and Exchange Commission said in a lessons-learned report. "However, that initial shock both uncovered and exacerbated other weaknesses in the global financial system."

Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard University economist, says the current difficulty has many mothers -- the housing bubble, the subprime problem and the fact that the value of U.S. imports has long outstripped the value of exports. The current account deficit -- the broadest measure of the trade deficit -- burgeoned, and the U.S. needed to borrow ever larger amounts of cash from abroad to fund it.

For years, Mr. Rogoff and like-minded economists harped that the U.S. current account deficit was unsustainable. But despite the belief that it would necessarily reverse, it kept growing through the first part of this decade, going from 3.6% of gross domestic product at the end of 1999 to a record 6.8% at the end of 2005. Lately, the deficit has seen a slight narrowing, but the combination of credit crisis and the economic downturn may have proved the catalyst for a faster, and potentially more dangerous, adjustment.

Pressures in one market spread rapidly to other, often more distant markets. "The dollar and subprime -- they're two sides of the same coin," says Princeton University economist Hyun Song Shin. Many U.S. hedge funds and financial institutions were speculating in mortgage-related securities with money that was ultimately borrowed in Japan, where interest rates have been low for years. He notes foreign banks' net liabilities in the yen interbank market surged between April 2006 and April 2007. As investments bought with money borrowed in Japan get sold and converted back into yen, he says, "we see both a fall in asset prices and a fall in the dollar."

The resulting blow to confidence threatens to further weaken lending, borrowing, spending and investment in the U.S. economy. "Hedge fund blowups have so far been one-off situations. One worry is that we'll cross some line and there'll be a systemic wave of fund failures. It's a reason why the market is so nervous," says John Tierney, credit derivatives strategist at Deutsche Bank.

Banks also are increasing the collateral they demand when they lend to hedge funds that hold municipal bonds. One hedge fund manager described what appears to be a coordinated effort by big investment banks to reduce their risk as they faced quarter-end pressures to cleanse their balance sheets. Lenders declared "by fiat," he said, that municipal-bond-fund managers needed to post more collateral to back their borrowings.

As a result, funds run by Blue River Asset Management, 1861 Capital Management and others circulated lists of assets to raise cash. The sell-off flooded the market with municipal bonds, making it more expensive for municipalities to borrow and upending the traditional relationship between tax-exempt municipal bonds and taxable U.S. Treasury bonds. For the first time in memory, yields on tax-exempt municipal bonds jumped above yields on taxable U.S. Treasury debt.

Now, many hedge fund managers say, access to borrowed money, essential for many of their investment strategies to work, has become virtually impossible.

Mohamed El-Erian, co-chief executive officer of Allianz SE's Pacific Investment Management Co., says the hedge-fund community is unwinding its leverage. "This will push more of them into 'survival mode,' further accentuating distressed sales and nervousness among the prime brokers," he wrote to his colleagues Thursday morning. "In such a world, the quality of the assets matters less than whether you can finance them [or] how liquid they are."

Monday, March 17, 2008

Wednesday, March 5, 2008

The Rise of the Middle Class Millionaire

I am interested in comments on this article from Market Watch. Text in bold is my emphasis.

Those with a net worth of between $1 million and $10 million -- that they have earned rather than inherited -- are being dubbed "middle-class millionaires," a group that has grown on the heels of the economic boom over the past couple decades.

Middle-class millionaires now account for 10% of the U.S. population, according Russ Alan Prince and Lewis Schiff, who coined the term for research purposes and a new book by that name. They studied almost 4,000 households to better understand attitudes, values and purchasing patterns.

Their findings include:

7.6% of American households, or 8.4 million households are middle-class millionaires

The average middle-class millionaire works 70 hours per week

Middle-class millionaires are five times more likely than the average worker to say they are always available for work

89% believes that anyone can attain wealth through hard work

62% believes that networking, or knowing many people, is the key to financial success

Nine out of 10 middle-class millionaires say they made a bad career or business move, but almost three-fourths say that was crucial to their business success

They are five times more likely than the average middle-class person to continue on in the same business course in spite an earlier failure

65% of middle-class millionaires characterize their approach to negotiating as "doing whatever you need to do to win"

They say they need a net worth of $24 million to feel wealthy, and $13.4 million to be considered rich.

Prince and Schiff also found that almost half of middle-class millionaires believe a child's academic achievements reflect one's success as a parent. Seventy-five percent of this group chose their home because of its school system. And only 14% of them trust the government.

This separates middle-class millionaires from the middle class in general: Only 16% of middle-class households were ready to put their own reputation on the lines when it comes to their kids' academic record, according to Prince and Schiff. More than half of middle-class households chose their homes because it was close to work. And an almost equal amount believes the government has their back, Prince and Schiff say.

The differences may be stark, but Prince and Schiff see that changing. They describe middle-class millionaires as "the rise of the new rich and how they are changing America." The changes they see are evident in four areas: hard work, networking, persistence and financial self-interest.

Trickle-down effect

These traits may differ from those in the middle class but their offspring, in the form of goods and services, are making their way "downstream."

"From life coaches to luxury vacation rentals, concierge medical care to high dollar prep course into the Ivy League [these things] are making their way downstream, steadily becoming available to a much broader population," Prince and Schiff say. "What was once the province of only the super rich is now being created and packaged for the 'downline' population or for those with fewer zeros in their net worth, but similar aspirations."

Collectively, the authors say, middle-class millionaires are influencing, advocating and reshaping the social, cultural and commercial landscape of our world.

It's a whole new level of keeping up with the Joneses.

Take the OnStar navigation system. It began as an emergency road service for high-end luxury vehicles. Now it's even offered on midrange trucks. Similar trends are occurring in real estate, vacations, airline travel and other services.

We may have to begin adding some new class structures in America. Otherwise we may all soon belong to the same one.

I am interested in comments on this article from Market Watch. Text in bold is my emphasis.

Those with a net worth of between $1 million and $10 million -- that they have earned rather than inherited -- are being dubbed "middle-class millionaires," a group that has grown on the heels of the economic boom over the past couple decades.

Middle-class millionaires now account for 10% of the U.S. population, according Russ Alan Prince and Lewis Schiff, who coined the term for research purposes and a new book by that name. They studied almost 4,000 households to better understand attitudes, values and purchasing patterns.

Their findings include:

7.6% of American households, or 8.4 million households are middle-class millionaires

The average middle-class millionaire works 70 hours per week

Middle-class millionaires are five times more likely than the average worker to say they are always available for work

89% believes that anyone can attain wealth through hard work

62% believes that networking, or knowing many people, is the key to financial success

Nine out of 10 middle-class millionaires say they made a bad career or business move, but almost three-fourths say that was crucial to their business success

They are five times more likely than the average middle-class person to continue on in the same business course in spite an earlier failure

65% of middle-class millionaires characterize their approach to negotiating as "doing whatever you need to do to win"

They say they need a net worth of $24 million to feel wealthy, and $13.4 million to be considered rich.

Prince and Schiff also found that almost half of middle-class millionaires believe a child's academic achievements reflect one's success as a parent. Seventy-five percent of this group chose their home because of its school system. And only 14% of them trust the government.

This separates middle-class millionaires from the middle class in general: Only 16% of middle-class households were ready to put their own reputation on the lines when it comes to their kids' academic record, according to Prince and Schiff. More than half of middle-class households chose their homes because it was close to work. And an almost equal amount believes the government has their back, Prince and Schiff say.

The differences may be stark, but Prince and Schiff see that changing. They describe middle-class millionaires as "the rise of the new rich and how they are changing America." The changes they see are evident in four areas: hard work, networking, persistence and financial self-interest.

Trickle-down effect

These traits may differ from those in the middle class but their offspring, in the form of goods and services, are making their way "downstream."

"From life coaches to luxury vacation rentals, concierge medical care to high dollar prep course into the Ivy League [these things] are making their way downstream, steadily becoming available to a much broader population," Prince and Schiff say. "What was once the province of only the super rich is now being created and packaged for the 'downline' population or for those with fewer zeros in their net worth, but similar aspirations."

Collectively, the authors say, middle-class millionaires are influencing, advocating and reshaping the social, cultural and commercial landscape of our world.

It's a whole new level of keeping up with the Joneses.

Take the OnStar navigation system. It began as an emergency road service for high-end luxury vehicles. Now it's even offered on midrange trucks. Similar trends are occurring in real estate, vacations, airline travel and other services.

We may have to begin adding some new class structures in America. Otherwise we may all soon belong to the same one.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

There Will Be a Large Private Equity Failure This Year

A British private equity insider believes that there will be at least one large private equity failure this year. The article is interesting because it goes into the causes of the credit crunch in private equity and most of the blame is placed on the industry itself. Text in bold is my emphasis. From the UK Telegraph:

In a speech taking shots at the whole industry, he said: "There will be large private equity failures this year. Absolutely guaranteed. This is a cyclical downturn for the industry. We are going to have very weak returns for a while.

"Companies will go bust and that is going to be a problem. We have got some savagely leveraged companies out there, and unless something else happens to distract them, the politicians will be back and we can look forward to more regulation and tax damaging this business."

Mr Moulton blamed industry players themselves for throwing out normal standards of due diligence and risk assessment during the recent boom years. "Buy-outs were done on mythical numbers like pro-forma, adjusted, normalised EBITDA, which almost always turned out to be 20pc higher than reality," he said. "We were buying false numbers and doing it willingly but the quality of what we were doing had come down. It's the same thing that was going on in the US sub-prime market."

Giving the opening speech at SuperReturn 2008, the major international conference for the private equity industry, Mr Moulton took aim at public relations executives, industry associations, accountants, mega funds and regulators. However, he saved most of his criticism for the banks.

"They bought all this rubbish themselves, most of which their senior managers didn't understand, and they have been left holding the baby with unsaleable, overpriced, over-enthusiastic debt. They are in trouble themselves. It's the same as the sub-prime salesman. They will sell anything to anyone, and they did. If you pay enough bonuses, people will do anything."

He said the image of private equity was of "rich, capitalist swine" but was dismissive of the report drawn up by Sir David Walker for the industry, which aimed to increase transparency and alter the perception of the industry. "The new pedestrian culture of the private equity world", he called it, saying that it would have no practical effect.

Mr Moulton was just one of a host of speakers who forecast no end to the current credit crisis. "I think we are seeing a meltdown in the credit markets that has some life in terms of the downside left to it," said Scott Sperling, co-president of Thomas H Lee.

He said it could take a long time for lending banks to shift the billions of dollars of debt they have been left with by the credit crunch.

His views were echoed by Hamilton James, chief operating officer of Blackstone, who said he was working on the basis of a US recession, and by Jonathan Nelson, of Providence Equity Partners, who said he believed a recession had started as long ago as December.

A British private equity insider believes that there will be at least one large private equity failure this year. The article is interesting because it goes into the causes of the credit crunch in private equity and most of the blame is placed on the industry itself. Text in bold is my emphasis. From the UK Telegraph:

In a speech taking shots at the whole industry, he said: "There will be large private equity failures this year. Absolutely guaranteed. This is a cyclical downturn for the industry. We are going to have very weak returns for a while.

"Companies will go bust and that is going to be a problem. We have got some savagely leveraged companies out there, and unless something else happens to distract them, the politicians will be back and we can look forward to more regulation and tax damaging this business."

Mr Moulton blamed industry players themselves for throwing out normal standards of due diligence and risk assessment during the recent boom years. "Buy-outs were done on mythical numbers like pro-forma, adjusted, normalised EBITDA, which almost always turned out to be 20pc higher than reality," he said. "We were buying false numbers and doing it willingly but the quality of what we were doing had come down. It's the same thing that was going on in the US sub-prime market."

Giving the opening speech at SuperReturn 2008, the major international conference for the private equity industry, Mr Moulton took aim at public relations executives, industry associations, accountants, mega funds and regulators. However, he saved most of his criticism for the banks.

"They bought all this rubbish themselves, most of which their senior managers didn't understand, and they have been left holding the baby with unsaleable, overpriced, over-enthusiastic debt. They are in trouble themselves. It's the same as the sub-prime salesman. They will sell anything to anyone, and they did. If you pay enough bonuses, people will do anything."

He said the image of private equity was of "rich, capitalist swine" but was dismissive of the report drawn up by Sir David Walker for the industry, which aimed to increase transparency and alter the perception of the industry. "The new pedestrian culture of the private equity world", he called it, saying that it would have no practical effect.

Mr Moulton was just one of a host of speakers who forecast no end to the current credit crisis. "I think we are seeing a meltdown in the credit markets that has some life in terms of the downside left to it," said Scott Sperling, co-president of Thomas H Lee.

He said it could take a long time for lending banks to shift the billions of dollars of debt they have been left with by the credit crunch.

His views were echoed by Hamilton James, chief operating officer of Blackstone, who said he was working on the basis of a US recession, and by Jonathan Nelson, of Providence Equity Partners, who said he believed a recession had started as long ago as December.

The Fed’s Rate Cuts Are Not Working

As stated here a number of times one cannot fight the “new” economic war with the weapons from the last war (the Great Depression). That is exactly what the Fed is doing and it is not working well. Admittedly, it keeps liquidity in the system, which is propping up the financial system, but it is not addressing the ultimate problem of bank losses. The issue of bank solvency will cause the banks to shrink, thereby decreasing new loan originations (the credit crunch) putting more pressure on economic growth. The original article has some interesting links (included here) and comments if you have the time. Text in bold is my emphasis. From the UK Telegraph:

The verdict is in. The Fed's emergency rate cuts in January have failed to halt the downward spiral towards a full-blown debt deflation. Much more drastic action will be needed.

Yields on two-year US Treasuries plummeted to 1.63pc on Friday in a flight to safety, foretelling financial winter.

The debt markets are freezing ever deeper, a full eight months into the crunch. Contagion is spreading into the safest pockets of the US credit universe.

It is hard to imagine a more plain-vanilla outfit than the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which manages bridges, bus terminals, and airports.The authority is a public body, backed by the two states. Yet it had to pay 20pc rates in February after the near closure of the $330bn (£166m) "term-auction" market. It had originally expected to pay 4.3pc, but that was aeons ago in financial time.

"I never thought I would see anything like this in my life," said James Steele, an HSBC economist in New York.

No sane mortal needs to know what term-auction means, except that it too became a tool of the US credit alchemists. Banks briefly used the market as laboratory for conjuring long-term loans at Alan Greenspan's giveaway short-term rates. It has come unstuck. Next in line is the $45trillion derivatives market for credit default swaps (CDS).

Last week, the spreads on high-yield US bonds vaulted to 718 basis points. The iTraxx Crossover index measuring corporate default risk in Europe smashed the 600 barrier. We are now far beyond the August spike.

Sub-prime debt is plumbing new depths. A-rated securities issued in early 2007 fell to a record 12.72pc of face value on Friday. The BBB tier fetched 10.42pc. The "toxic" tranches are worthless.

Why won't it end? Because US house prices are in free fall. The Case-Shiller index for the 20 biggest cities dropped 9.1pc year-on-year in December. The annualised rate of fall was 18pc in the fourth quarter, and gathering speed.

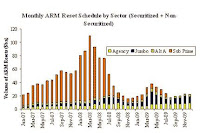

As the graph shows below, US households are only halfway through the tsunami of rate resets - 300 basis points upwards - on teaser loans. The UK hedge fund Peloton Partners misjudged this fresh leg of the crunch. After an 87pc profit last year betting against sub-prime, it switched sides to play the rebound. Last week it had to liquidate a $2bn fund.

Like many, Peloton thought Fed rate cuts from 5.25pc to 3pc (with more to come) would end the panic. But this is not a normal downturn, subject to normal recovery. Leverage is too extreme. Bank capital is too eroded. Monetary traction eludes the Fed. An "Austrian" purge is under way.

UBS says the cost of the credit debacle will reach $600bn. "Leveraged risk is a cancer in this market."

Try $1trillion, says New York professor Nouriel Roubini. Contagion is moving up the ladder to prime mortgages, commercial property, home equity loans, car loans, credit cards and student loans. We have not even begun Wave Two: the British, Club Med, East European, and Antipodean house busts.

and student loans. We have not even begun Wave Two: the British, Club Med, East European, and Antipodean house busts.

As the once unthinkable unfolds, the leaders of global finance dither. The Europeans are frozen in the headlights: trembling before a false inflation; cowed by an atavistic Bundesbank; waiting passively for the Atlantic storm to hit.

Half the eurozone is grinding to a halt. Italy is slipping into recession. Property prices are flat or falling in Ireland, Spain, France, southern Italy and now Germany. French consumer moral is the lowest in 20 years.

The euro fetches $1.52 (from $0.82 in 2000), beyond the pain threshold for aircraft, cars, luxury goods and textiles. The manufacturing base of southern Europe is largely below water. As Le Figaro wrote last week, the survival of monetary union is in doubt. Yet still, the ECB waits; still the German-bloc governors breathe fire about inflation. "There probably will be some bank failures," said Ben Bernanke. He knows perfectly well that the US price spike is a bogus scare, the tail-end of a food and fuel shock.

"I expect inflation to come down. I don't think we're anywhere near the situation in the 1970s," he told Congress.

Indeed not. Real wages are being squeezed. Oil and "Ags" are acting as a tax. December unemployment jumped at the fastest rate in a quarter century.

The greater risk is slump, says Princetown Professor Paul Krugman. "The Fed is studying the Japanese experience with zero rates very closely. The problem is that if they want to cut rates as aggressively as they did in the early 1990s and 2001, they have to go below zero."

This means "quantitative easing" as it was called in Japan. As Ben Bernanke spelled out in November 2002, the Fed can inject money by purchasing great chunks of the bond market.

Section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act allows the bank - in "exigent circumstances" - to lend money to anybody, and take upon itself the credit risk. It has not done so since the 1930s.

Ultimately the big guns have the means to stop descent into an economic Ice Age. But will they act in time?

"We are becoming increasingly concerned that the authorities in the world do not get it," said Bernard Connolly, global strategist at Banque AIG.

"The extent of de-leveraging involves a wholesale destruction of credit. The risk is that the 'shadow banking system' completely collapses," he said.

For the first time since this Greek tragedy began, I am now really frightened. (No need to be frightened, the trick is to know when to duck.)

As stated here a number of times one cannot fight the “new” economic war with the weapons from the last war (the Great Depression). That is exactly what the Fed is doing and it is not working well. Admittedly, it keeps liquidity in the system, which is propping up the financial system, but it is not addressing the ultimate problem of bank losses. The issue of bank solvency will cause the banks to shrink, thereby decreasing new loan originations (the credit crunch) putting more pressure on economic growth. The original article has some interesting links (included here) and comments if you have the time. Text in bold is my emphasis. From the UK Telegraph:

The verdict is in. The Fed's emergency rate cuts in January have failed to halt the downward spiral towards a full-blown debt deflation. Much more drastic action will be needed.

Yields on two-year US Treasuries plummeted to 1.63pc on Friday in a flight to safety, foretelling financial winter.

The debt markets are freezing ever deeper, a full eight months into the crunch. Contagion is spreading into the safest pockets of the US credit universe.

It is hard to imagine a more plain-vanilla outfit than the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which manages bridges, bus terminals, and airports.The authority is a public body, backed by the two states. Yet it had to pay 20pc rates in February after the near closure of the $330bn (£166m) "term-auction" market. It had originally expected to pay 4.3pc, but that was aeons ago in financial time.

"I never thought I would see anything like this in my life," said James Steele, an HSBC economist in New York.

No sane mortal needs to know what term-auction means, except that it too became a tool of the US credit alchemists. Banks briefly used the market as laboratory for conjuring long-term loans at Alan Greenspan's giveaway short-term rates. It has come unstuck. Next in line is the $45trillion derivatives market for credit default swaps (CDS).

Last week, the spreads on high-yield US bonds vaulted to 718 basis points. The iTraxx Crossover index measuring corporate default risk in Europe smashed the 600 barrier. We are now far beyond the August spike.

Sub-prime debt is plumbing new depths. A-rated securities issued in early 2007 fell to a record 12.72pc of face value on Friday. The BBB tier fetched 10.42pc. The "toxic" tranches are worthless.

Why won't it end? Because US house prices are in free fall. The Case-Shiller index for the 20 biggest cities dropped 9.1pc year-on-year in December. The annualised rate of fall was 18pc in the fourth quarter, and gathering speed.

As the graph shows below, US households are only halfway through the tsunami of rate resets - 300 basis points upwards - on teaser loans. The UK hedge fund Peloton Partners misjudged this fresh leg of the crunch. After an 87pc profit last year betting against sub-prime, it switched sides to play the rebound. Last week it had to liquidate a $2bn fund.

Like many, Peloton thought Fed rate cuts from 5.25pc to 3pc (with more to come) would end the panic. But this is not a normal downturn, subject to normal recovery. Leverage is too extreme. Bank capital is too eroded. Monetary traction eludes the Fed. An "Austrian" purge is under way.

UBS says the cost of the credit debacle will reach $600bn. "Leveraged risk is a cancer in this market."

Try $1trillion, says New York professor Nouriel Roubini. Contagion is moving up the ladder to prime mortgages, commercial property, home equity loans, car loans, credit cards

As the once unthinkable unfolds, the leaders of global finance dither. The Europeans are frozen in the headlights: trembling before a false inflation; cowed by an atavistic Bundesbank; waiting passively for the Atlantic storm to hit.

Half the eurozone is grinding to a halt. Italy is slipping into recession. Property prices are flat or falling in Ireland, Spain, France, southern Italy and now Germany. French consumer moral is the lowest in 20 years.

The euro fetches $1.52 (from $0.82 in 2000), beyond the pain threshold for aircraft, cars, luxury goods and textiles. The manufacturing base of southern Europe is largely below water. As Le Figaro wrote last week, the survival of monetary union is in doubt. Yet still, the ECB waits; still the German-bloc governors breathe fire about inflation. "There probably will be some bank failures," said Ben Bernanke. He knows perfectly well that the US price spike is a bogus scare, the tail-end of a food and fuel shock.

"I expect inflation to come down. I don't think we're anywhere near the situation in the 1970s," he told Congress.

Indeed not. Real wages are being squeezed. Oil and "Ags" are acting as a tax. December unemployment jumped at the fastest rate in a quarter century.

The greater risk is slump, says Princetown Professor Paul Krugman. "The Fed is studying the Japanese experience with zero rates very closely. The problem is that if they want to cut rates as aggressively as they did in the early 1990s and 2001, they have to go below zero."

This means "quantitative easing" as it was called in Japan. As Ben Bernanke spelled out in November 2002, the Fed can inject money by purchasing great chunks of the bond market.

Section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act allows the bank - in "exigent circumstances" - to lend money to anybody, and take upon itself the credit risk. It has not done so since the 1930s.

Ultimately the big guns have the means to stop descent into an economic Ice Age. But will they act in time?

"We are becoming increasingly concerned that the authorities in the world do not get it," said Bernard Connolly, global strategist at Banque AIG.

"The extent of de-leveraging involves a wholesale destruction of credit. The risk is that the 'shadow banking system' completely collapses," he said.

For the first time since this Greek tragedy began, I am now really frightened. (No need to be frightened, the trick is to know when to duck.)

Monday, March 3, 2008

This Weekend’s Contemplation – The Financial Institutions Will Shrink by $2T - Part 2

Yesterday’s post on the cuts the banks would have to incur as losses mounted seemed to garner a lot of interest so I decided to look into it further. I found the article below from Market Watch, which shed more light on the subject. I also found a copy of the paper at a Brandeis University site.

Finally, I am beginning to see stories in the press that jive with what I am being told by contacts in the commercial and investment banking industry. Since the beginning the year the risk managers or others close to the capital markets they are all very pessimistic. (I did not use “extremely” pessimistic because I may have to use that term in a few months and I did not want to run out of adjectives.) Make no mistake we are living in historic times in terms of the economy. As a result there is no clear path to success. In addition, many of the policies that are now being deployed (rate cuts, stimulus packages, etc.) are methods used to fight the last war, the Great Depression, and this situation is different.

The economic impact of the mortgage crisis and credit crunch will be huge, and it has barely begun, a new study prepared by several prominent economists and released Friday has concluded.

"Feedback from the financial market turmoil to the real economy could be substantial," it said. Unless they can quickly recapitalize, banks are likely to cut back their lending to consumers and businesses by more than $1 trillion, cutting economic growth by more than a percentage point over the next 12 months.

After an initial period where several financial markets seemed immune from the crisis, the credit crunch is now gathering storm.

The report estimates that the credit crunch is expected to push down growth by 1.3 percentage points over the next 12 months.

Almost as alarming is the report's conclusion that this crisis is unique in the annals of U.S. economic history but now may serve as the template for more crises to come.

What is different this time is the amount of leverage. Bank balance sheets were forced to expand in the wake of the mortgage crisis, as off-balance-sheet investments were forced onto their books.

This so-called "unwanted lending" is set to reduce bank loans to business and consumers.

The paper estimates that total mortgage credit losses will cost $400 billion, up from initial estimates in August of $150 billion. Roughly 50%, or $200 billion, will be on the books of U.S. banks and securities firms.

This will result in an estimated contraction in lending of $1.13 trillion.

UBS analysts published a report Friday saying global losses could be $600 billion.

Banks have a choice to contract their balance sheets so that their capital on hand is sufficient, or else seek new capital from sovereign wealth funds or other investors.

There is little chance that the economic environment will improve any time soon to avoid this choice, the study said.

As of the end of January, banks had raised $75 billion in new capital and suffered $121 billion in losses.

The report urges banks to cut their dividends to preserve their existing capital. Central banks and governments should encourage this action across the globe so that there is no competitive disadvantage or stigma from the reduction.

For U.S. regulators, the study suggests the resumption of a monthly survey that details how much bank lending is truly voluntary.

A worse-than-expected economic outlook would cause a downward revision to these estimates.

A sharp decline in home prices could lead to many U.S. homeowners with negative equity, the report said.

At the moment, 50 million households have mortgages. If home prices drop 15%, it would put 21% of these mortgages, or $2.6 trillion, underwater.

The findings were presented at a forum organized by the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. Presenters included Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs, Anil Kashyap of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University.

At the forum, two top Fed officials -- Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Fed Governor Frederic Mishkin -- were asked to respond to the paper. Both said they agreed with the basic story.

"I agree ... that relatively small losses in one sector of the credit market can have outsized impact on aggregate economic activity if they case a disruption to the financial system that leads to an amplified impact on lending," Mishkin said.

In fact, Rosengren said the authors may have underestimated the economic impact because of the risk of rising unemployment and a sharper drop in home prices.

At the moment, the consensus forecast of economists is for the U.S. to skirt a recession with only a small decline in home prices nationwide.

Rosengren said it was prudent for the Fed to take account of the downside risks to the economy in crafting its policy. He said the rate cuts to date have helped keep home prices from falling and the unemployment rate from rising.

So far, Rosengren said, the capital losses in the banking system have been concentrated in large banks. Small and medium-sized firms have not complained about a lack of credit.

In a separate speech, Dennis Lockhart, president of the Atlanta Fed, said that the financial markets remain fragile and vulnerable to shock.

"Looking ahead, I believe resolution of the current financial market problems requires some stabilization of U.S. housing markets. At this time, it's difficult to determine when that stability will materialize," Lockhart said in a luncheon speech in Atlanta.

Yesterday’s post on the cuts the banks would have to incur as losses mounted seemed to garner a lot of interest so I decided to look into it further. I found the article below from Market Watch, which shed more light on the subject. I also found a copy of the paper at a Brandeis University site.

Finally, I am beginning to see stories in the press that jive with what I am being told by contacts in the commercial and investment banking industry. Since the beginning the year the risk managers or others close to the capital markets they are all very pessimistic. (I did not use “extremely” pessimistic because I may have to use that term in a few months and I did not want to run out of adjectives.) Make no mistake we are living in historic times in terms of the economy. As a result there is no clear path to success. In addition, many of the policies that are now being deployed (rate cuts, stimulus packages, etc.) are methods used to fight the last war, the Great Depression, and this situation is different.

The economic impact of the mortgage crisis and credit crunch will be huge, and it has barely begun, a new study prepared by several prominent economists and released Friday has concluded.

"Feedback from the financial market turmoil to the real economy could be substantial," it said. Unless they can quickly recapitalize, banks are likely to cut back their lending to consumers and businesses by more than $1 trillion, cutting economic growth by more than a percentage point over the next 12 months.

After an initial period where several financial markets seemed immune from the crisis, the credit crunch is now gathering storm.

The report estimates that the credit crunch is expected to push down growth by 1.3 percentage points over the next 12 months.

Almost as alarming is the report's conclusion that this crisis is unique in the annals of U.S. economic history but now may serve as the template for more crises to come.

What is different this time is the amount of leverage. Bank balance sheets were forced to expand in the wake of the mortgage crisis, as off-balance-sheet investments were forced onto their books.

This so-called "unwanted lending" is set to reduce bank loans to business and consumers.

The paper estimates that total mortgage credit losses will cost $400 billion, up from initial estimates in August of $150 billion. Roughly 50%, or $200 billion, will be on the books of U.S. banks and securities firms.

This will result in an estimated contraction in lending of $1.13 trillion.

UBS analysts published a report Friday saying global losses could be $600 billion.

Banks have a choice to contract their balance sheets so that their capital on hand is sufficient, or else seek new capital from sovereign wealth funds or other investors.

There is little chance that the economic environment will improve any time soon to avoid this choice, the study said.

As of the end of January, banks had raised $75 billion in new capital and suffered $121 billion in losses.

The report urges banks to cut their dividends to preserve their existing capital. Central banks and governments should encourage this action across the globe so that there is no competitive disadvantage or stigma from the reduction.

For U.S. regulators, the study suggests the resumption of a monthly survey that details how much bank lending is truly voluntary.

A worse-than-expected economic outlook would cause a downward revision to these estimates.

A sharp decline in home prices could lead to many U.S. homeowners with negative equity, the report said.

At the moment, 50 million households have mortgages. If home prices drop 15%, it would put 21% of these mortgages, or $2.6 trillion, underwater.

The findings were presented at a forum organized by the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. Presenters included Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs, Anil Kashyap of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University.

At the forum, two top Fed officials -- Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Fed Governor Frederic Mishkin -- were asked to respond to the paper. Both said they agreed with the basic story.

"I agree ... that relatively small losses in one sector of the credit market can have outsized impact on aggregate economic activity if they case a disruption to the financial system that leads to an amplified impact on lending," Mishkin said.

In fact, Rosengren said the authors may have underestimated the economic impact because of the risk of rising unemployment and a sharper drop in home prices.

At the moment, the consensus forecast of economists is for the U.S. to skirt a recession with only a small decline in home prices nationwide.

Rosengren said it was prudent for the Fed to take account of the downside risks to the economy in crafting its policy. He said the rate cuts to date have helped keep home prices from falling and the unemployment rate from rising.

So far, Rosengren said, the capital losses in the banking system have been concentrated in large banks. Small and medium-sized firms have not complained about a lack of credit.

In a separate speech, Dennis Lockhart, president of the Atlanta Fed, said that the financial markets remain fragile and vulnerable to shock.

"Looking ahead, I believe resolution of the current financial market problems requires some stabilization of U.S. housing markets. At this time, it's difficult to determine when that stability will materialize," Lockhart said in a luncheon speech in Atlanta.

Sunday, March 2, 2008

This Weekend’s Contemplation – The Financial Institutions Will Shrink by $2T

The post below from the WSJ discusses potential losses from the mortgage industry and the resulting decrease in financial institution assets. Using three different methods to forecast total mortgage losses it appears that $400B seems to be a consistent estimate. The last I heard the financial institutions had written off about $163B. That means that the financial institutions are only 40% of the way done and look at the problems it is causing. Ultimately, this will cause the financial institutions to shrink their asset size by about $2T to accommodate the losses. It is estimated that this will cut about 1% – 1.5% from economic growth. Text in bold is my emphasis. Also the a copy of the original study can be found at a Brandeis University site.

Mortgage losses, compounded by contemporary risk-management and accounting practices, could prompt banks and other lenders to shrink their lending and other assets by $2 trillion, a study concludes.

The resulting withdrawal of credit could knock one to 1.5 percentage points off economic growth, compounding the impact of collapsing home construction and softer consumer spending due to lower home wealth, the study said. It was presented Friday at a forum in New York on the Federal Reserve organized by the Brandeis International Business School and the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

The study is one of the most exhaustive efforts to date to pinpoint the extent and impact of mortgage losses.

But the latest study argues the losses will be far larger -- about $400 billion -- and cause much more damage than if they had occurred in stocks or corporate bonds. That is because about half the losses will be borne by banks and other highly leveraged institutions, which hold equity and other capital of just 4% to 10% of total assets.

For each dollar of loss not made up for by new capital, these institutions will have to shrink their balance sheets by $10 to $25 by reducing lending or selling securities. They would do that not just in order to keep their capital ratios steady, but also to raise those ratios to align with risk-management practices.

"The interaction of marking assets to their market prices and the risk-management practices of levered financial institutions" amplifies the impact of the initial losses, according to the authors, David Greenlaw of Morgan Stanley, Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Anil Kashyap of the University of Chicago and Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University. "The feedback from the financial market turmoil to the real economy could be substantial."

The authors calculate mortgage losses three ways: by extrapolating losses on earlier subprime mortgages to more recently issued mortgages and adjusting for a 15% cumulative decline in home prices; by looking at the size of losses discounted by prices of derivatives based on subprime mortgages; and by extrapolating the experience of California, Texas and Massachusetts with large home-price declines. All three methods yielded total losses (defaulted loans minus value recovered from foreclosed homes) of about $400 billion.

After examining the mortgages' distribution, they concluded about half is held by "leveraged" institutions such as banks, thrifts, securities dealers and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Based on recent experience, they calculate such institutions on average will want to boost their capital-to-asset ratios 5% because of increased risk. Even assuming they offset half their losses by raising $100 billion in new capital, these institutions still will try to shrink their assets, now about $20.5 trillion, by about $2 trillion.

The study helps quantify a phenomenon called the financial accelerator, first coined by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke as an academic and now a major factor in his decision recently to speed up interest-rate cuts. Mr. Bernanke told Congress this past week that the accelerator is "perhaps even more enhanced now than usual in that the credit conditions in the financial market are creating some restraint on growth. And slower growth, in turn, is concerning to financial markets because it may mean the credit quality is declining."

Mortgage losses, compounded by contemporary risk-management and accounting practices, could prompt banks and other lenders to shrink their lending and other assets by $2 trillion, a study concludes.

The resulting withdrawal of credit could knock one to 1.5 percentage points off economic growth, compounding the impact of collapsing home construction and softer consumer spending due to lower home wealth, the study said. It was presented Friday at a forum in New York on the Federal Reserve organized by the Brandeis International Business School and the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

The study is one of the most exhaustive efforts to date to pinpoint the extent and impact of mortgage losses.

In the initial stages of the crisis, some optimists noted that early estimates of subprime losses of $50 billion to $100 billion were about the same as one bad day in the stock market.

But the latest study argues the losses will be far larger -- about $400 billion -- and cause much more damage than if they had occurred in stocks or corporate bonds. That is because about half the losses will be borne by banks and other highly leveraged institutions, which hold equity and other capital of just 4% to 10% of total assets.

For each dollar of loss not made up for by new capital, these institutions will have to shrink their balance sheets by $10 to $25 by reducing lending or selling securities. They would do that not just in order to keep their capital ratios steady, but also to raise those ratios to align with risk-management practices.

"The interaction of marking assets to their market prices and the risk-management practices of levered financial institutions" amplifies the impact of the initial losses, according to the authors, David Greenlaw of Morgan Stanley, Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Anil Kashyap of the University of Chicago and Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University. "The feedback from the financial market turmoil to the real economy could be substantial."

The authors calculate mortgage losses three ways: by extrapolating losses on earlier subprime mortgages to more recently issued mortgages and adjusting for a 15% cumulative decline in home prices; by looking at the size of losses discounted by prices of derivatives based on subprime mortgages; and by extrapolating the experience of California, Texas and Massachusetts with large home-price declines. All three methods yielded total losses (defaulted loans minus value recovered from foreclosed homes) of about $400 billion.

After examining the mortgages' distribution, they concluded about half is held by "leveraged" institutions such as banks, thrifts, securities dealers and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Based on recent experience, they calculate such institutions on average will want to boost their capital-to-asset ratios 5% because of increased risk. Even assuming they offset half their losses by raising $100 billion in new capital, these institutions still will try to shrink their assets, now about $20.5 trillion, by about $2 trillion.

The study helps quantify a phenomenon called the financial accelerator, first coined by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke as an academic and now a major factor in his decision recently to speed up interest-rate cuts. Mr. Bernanke told Congress this past week that the accelerator is "perhaps even more enhanced now than usual in that the credit conditions in the financial market are creating some restraint on growth. And slower growth, in turn, is concerning to financial markets because it may mean the credit quality is declining."

(Double click to enlarge.)

Saturday, March 1, 2008

More Recession Alarms Are Going Off

The various recession alarms continue to go off for the US economy. Let me add one more thing to all these measures. I work in the risk sector of the financial industry and there are 2 things that I am seeing: 1) the risk people are becoming more pessimistic, while the marketing people are becoming more optimistic (always a bad sign), 2) the employment opportunities for risk people is usually a very vibrant market. I am hearing that the market for risk people has really slowed down. All the pieces of the puzzle are beginning to come together and I suspect by early summer we will know what is happening for sure. Text in bold is my emphasis. From Yahoo:

The alarm bells of U.S. recession rang louder on Friday as reports showed business activity in the U.S. Midwest plummeted in February and consumer sentiment slumped to a 16-year low.

More grim news poured in from the inflation front, with government data indicating consumers were struggling in January to keep ahead of robust price growth, which remained uncomfortably high by standards normally associated with the Federal Reserve.

The National Association of Purchasing Managers-Chicago said its index of regional business conditions tumbled to 44.5, its lowest since December 2001, from 51.5 in January. The result was well below the level of 50 that separates growth from contraction.

"It looks like there's been a reversal of fortune for the manufacturing sector from last month and the economy appears to have fallen off a cliff," said Chris Rupkey, senior financial economist, Bank of Tokyo/Mitsubishi, New York, referring to the Chicago PMI report.

"This is just the latest piece of evidence that the U.S. economy is teetering on the edge of recession."

The Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said its main index of consumer sentiment fell to 70.8 in February from 78.4 in January and was the lowest since February 1992.

A measure of consumers' expectations also hit a 16-year low while worries about their ability to makes ends meet and the overall economy were as bad as they have been in decades, the Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said.

"Consumer confidence remained at the same low level that was recorded during the recession periods of the mid-1970s, the early 1980s and the early 1990s," the Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said in a statement.

The Chicago PMI release comes after regional manufacturing reports have suggested the onset of recessionary conditions in the factory sector.

The results have driven expectations that next week's national gauge of manufacturing from the Institute for Supply Management will show a contraction.

Many analysts consider the NAPM-Chicago survey a factory report since the region is relatively industrialized. But service sector companies and non-profits are polled too.

U.S. consumer spending rose more than expected in January, but the gain was eaten up by swiftly rising prices, the government said in a report that underscored the pressure households face.

The Commerce Department said personal spending rose 0.4 percent last month, while personal income increased by 0.3 percent.

When adjusted for inflation, however, spending was unchanged, due largely to rising food and energy costs.

The personal consumption expenditure price index, a key inflation gauge, rose 2.2 percent year-over-year when food and energy items are excluded. This matched the prior month's "core" inflation rate but remained above the Fed's perceived comfort zone, which tops out at about 2 percent.

The University of Michigan report showed rising prices were a concern for consumers and one-year inflation expectations jumped to 3.6 percent from 3.4 percent in January.

"Expectations for personal finances as well as for the entire economy are now as pessimistic as any time during the past quarter century," the University of Michigan report said.

The various recession alarms continue to go off for the US economy. Let me add one more thing to all these measures. I work in the risk sector of the financial industry and there are 2 things that I am seeing: 1) the risk people are becoming more pessimistic, while the marketing people are becoming more optimistic (always a bad sign), 2) the employment opportunities for risk people is usually a very vibrant market. I am hearing that the market for risk people has really slowed down. All the pieces of the puzzle are beginning to come together and I suspect by early summer we will know what is happening for sure. Text in bold is my emphasis. From Yahoo:

The alarm bells of U.S. recession rang louder on Friday as reports showed business activity in the U.S. Midwest plummeted in February and consumer sentiment slumped to a 16-year low.

More grim news poured in from the inflation front, with government data indicating consumers were struggling in January to keep ahead of robust price growth, which remained uncomfortably high by standards normally associated with the Federal Reserve.

The National Association of Purchasing Managers-Chicago said its index of regional business conditions tumbled to 44.5, its lowest since December 2001, from 51.5 in January. The result was well below the level of 50 that separates growth from contraction.

"It looks like there's been a reversal of fortune for the manufacturing sector from last month and the economy appears to have fallen off a cliff," said Chris Rupkey, senior financial economist, Bank of Tokyo/Mitsubishi, New York, referring to the Chicago PMI report.

"This is just the latest piece of evidence that the U.S. economy is teetering on the edge of recession."

The Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said its main index of consumer sentiment fell to 70.8 in February from 78.4 in January and was the lowest since February 1992.

A measure of consumers' expectations also hit a 16-year low while worries about their ability to makes ends meet and the overall economy were as bad as they have been in decades, the Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said.

"Consumer confidence remained at the same low level that was recorded during the recession periods of the mid-1970s, the early 1980s and the early 1990s," the Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers said in a statement.

The Chicago PMI release comes after regional manufacturing reports have suggested the onset of recessionary conditions in the factory sector.

The results have driven expectations that next week's national gauge of manufacturing from the Institute for Supply Management will show a contraction.

Many analysts consider the NAPM-Chicago survey a factory report since the region is relatively industrialized. But service sector companies and non-profits are polled too.

U.S. consumer spending rose more than expected in January, but the gain was eaten up by swiftly rising prices, the government said in a report that underscored the pressure households face.

The Commerce Department said personal spending rose 0.4 percent last month, while personal income increased by 0.3 percent.

When adjusted for inflation, however, spending was unchanged, due largely to rising food and energy costs.

The personal consumption expenditure price index, a key inflation gauge, rose 2.2 percent year-over-year when food and energy items are excluded. This matched the prior month's "core" inflation rate but remained above the Fed's perceived comfort zone, which tops out at about 2 percent.

The University of Michigan report showed rising prices were a concern for consumers and one-year inflation expectations jumped to 3.6 percent from 3.4 percent in January.

"Expectations for personal finances as well as for the entire economy are now as pessimistic as any time during the past quarter century," the University of Michigan report said.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)