Bankrate.com Suvey Shows People Do Not Save Enough

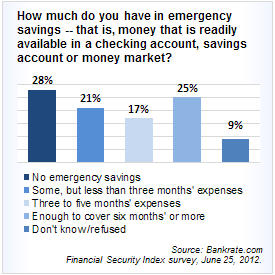

A recent survey by Bankrate.com shows that consumers have insufficient savings. 28% of consumers have no emergency savings and 2/3s have less than 6 months of savings. The numbers also show that this is closely tied to education level. The survey also acknowledges that for the last few years people have probably been forgoing savings to liquidate their debt. I find these types of demographics to be fascinating because regardless of "the opinions" you hear on the news, this is what is actually happening on the ground.

If people are actively retiring debt and then will begin to rebuild their savings, what does this say about economic growth for the next few years? I would have to vote slow.

The article is in italics and the bold is my emphasis.

From Bankrate.com:

Have Americans already forgotten the lessons learned in the financial crisis? The number of people with no money saved for emergencies has risen to 28 percent, up from 24 percent a year ago, according to Bankrate's Financial Security Index.

About 1 in 5 people are slightly better off, with enough savings in an emergency fund to cover less than three months of expenses, while 42 percent of those polled say they have at least three months' worth of cash saved.

Income and education matter

The general rule of thumb calls for enough cash to cover six months of living expenses. It depends who you ask, though. The recession prompted many financial advisers to boost that recommendation to 12 months' worth or more.

Not surprisingly, earning more than $75,000 per year vastly increases the odds of hitting the minimum recommendation of six months; 45 percent of high-income earners say they've reached or surpassed that mark.

Only 9 percent of these high earners say they have no rainy-day fund, compared to 52 percent of those earning less than $30,000.

A college degree is also fairly predictive of emergency fund savings: 41 percent of college graduates report enough savings to cover expenses for six months or more, versus 14 percent of those with a high school education.

While Americans may be struggling to save money, the collective debt load is smaller than it was several years ago, particularly when it comes to revolving accounts such as credit cards.

Between 2008 and 2010, consumers significantly paid down revolving credit accounts, according to figures from the Federal Reserve's April report on consumer credit.

Rather than stocking household coffers with extra funds, consumers who are now lacking substantial emergency funds may have used extra money to service debt instead.

"While the debts are down quite significantly on a household basis from prior years' levels and the households are much better off, I believe that this drop in debts came at the expense of savings," says Robert Fuest, chief operating officer and head of investment research at Landor & Fuest Capital Managers in New York.

Now that debt loads are lighter, the new challenge is to build up savings to avoid falling back into a cycle of debt.

Consumers are constantly barraged by marketing, none of which espouse living below your means and managing money responsibly.

"Many Americans used debt to fund about 20 percent of their lifestyle choices. They were running cash-flow negative, in essence," Fuest says.

Scaling back spending doesn't happen overnight, particularly in a society where the economy is powered by ever-increasing consumer demand.

It can take some time to change the mindset that leads to overspending, but there's an easy shortcut to boosting savings: automation.

"If you have an employer that can split out the amount that you are taking home and force-feed savings into an account that is out of sight and out of mind, I think that is one of the best ways," says Elliot Herman, CFP and partner at PRW Wealth Management in Quincy, Mass.

Alternatively, if your employer doesn't offer the option of splitting your direct deposit, an automatic transfer can be set up from your primary checking account to a savings account on the same day you're paid. The end result is the same; the money is spirited away before it's available to be spent.

For most people, establishing an emergency fund is a process in which a small pile of savings gradually grows into a larger one.

Keeping emergency savings fairly liquid is important, but once the fund reaches critical mass, savers may want more yield than they can find in a savings account or money market account.

With a sizable pot of money saved, placing a portion into a short-term bond fund could be a good idea, according to Herman.

"I would be wary of some of the higher-yielding short-term bond funds; those could have minefields within them that we don't know about right now. I don't think they're worth the risk. But I think there is something in between those and an ultrasafe savings account that is higher quality and is worth the risk," he says.

Yield should be secondary to liquidity, though. In general, earning a decent return on your savings is less important than simply having funds at the ready.

In the recession, Americans saw "how fast things can change, and they change beyond your control," says Susan Hirshman, president of consulting firm SHE LTD and author of "Does This Make My Assets Look Fat?"

"The only person responsible for you is you. You really can't rely on anyone," she says. With millions still out of work, home values still depressed and a fog of uncertainty around government-sponsored safety nets, there should be enough out there to scare people into saving.

Saving versus paying down debt

Between 2008 and 2010, consumers significantly paid down revolving credit accounts, according to figures from the Federal Reserve's April report on consumer credit.

Rather than stocking household coffers with extra funds, consumers who are now lacking substantial emergency funds may have used extra money to service debt instead.

"While the debts are down quite significantly on a household basis from prior years' levels and the households are much better off, I believe that this drop in debts came at the expense of savings," says Robert Fuest, chief operating officer and head of investment research at Landor & Fuest Capital Managers in New York.

Now that debt loads are lighter, the new challenge is to build up savings to avoid falling back into a cycle of debt.

Breaking bad habits

"Many Americans used debt to fund about 20 percent of their lifestyle choices. They were running cash-flow negative, in essence," Fuest says.

Scaling back spending doesn't happen overnight, particularly in a society where the economy is powered by ever-increasing consumer demand.

It can take some time to change the mindset that leads to overspending, but there's an easy shortcut to boosting savings: automation.

"If you have an employer that can split out the amount that you are taking home and force-feed savings into an account that is out of sight and out of mind, I think that is one of the best ways," says Elliot Herman, CFP and partner at PRW Wealth Management in Quincy, Mass.

Alternatively, if your employer doesn't offer the option of splitting your direct deposit, an automatic transfer can be set up from your primary checking account to a savings account on the same day you're paid. The end result is the same; the money is spirited away before it's available to be spent.

Where to park your emergency fund

Keeping emergency savings fairly liquid is important, but once the fund reaches critical mass, savers may want more yield than they can find in a savings account or money market account.

With a sizable pot of money saved, placing a portion into a short-term bond fund could be a good idea, according to Herman.

"I would be wary of some of the higher-yielding short-term bond funds; those could have minefields within them that we don't know about right now. I don't think they're worth the risk. But I think there is something in between those and an ultrasafe savings account that is higher quality and is worth the risk," he says.

Yield should be secondary to liquidity, though. In general, earning a decent return on your savings is less important than simply having funds at the ready.

In the recession, Americans saw "how fast things can change, and they change beyond your control," says Susan Hirshman, president of consulting firm SHE LTD and author of "Does This Make My Assets Look Fat?"

"The only person responsible for you is you. You really can't rely on anyone," she says. With millions still out of work, home values still depressed and a fog of uncertainty around government-sponsored safety nets, there should be enough out there to scare people into saving.

From: Bankrate.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment